African Period and Primitivism (1906 - 1910)

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the European cultural elite were discovering African, Micronesian and Native American art. African artifacts were being brought back to Paris museums following the expansion of the French empire into Africa. The press was abuzz with exaggerated stories of cannibalism and exotic tales about the African kingdom of Dahomey. The mistreatment of Africans in the Belgian Congo was exposed in Joseph Conrad's popular book, Heart of Darkness.

Artists such as Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse and Picasso were intrigued and inspired by the stark power and simplicity of styles of "primitive" cultures. Around 1906, Picasso, Matisse, Derain and other Paris-based artists had acquired an interest in Primitivism, Iberian sculpture, African art and tribal masks, in part due to the works of Paul Gauguin that had recently achieved recognition in Paris's avant-garde circles. Gauguin's powerful posthumous retrospective exhibitions at the Salon d'Automne in Paris in 1903 and 1906 had a powerful influence on Picasso's paintings .

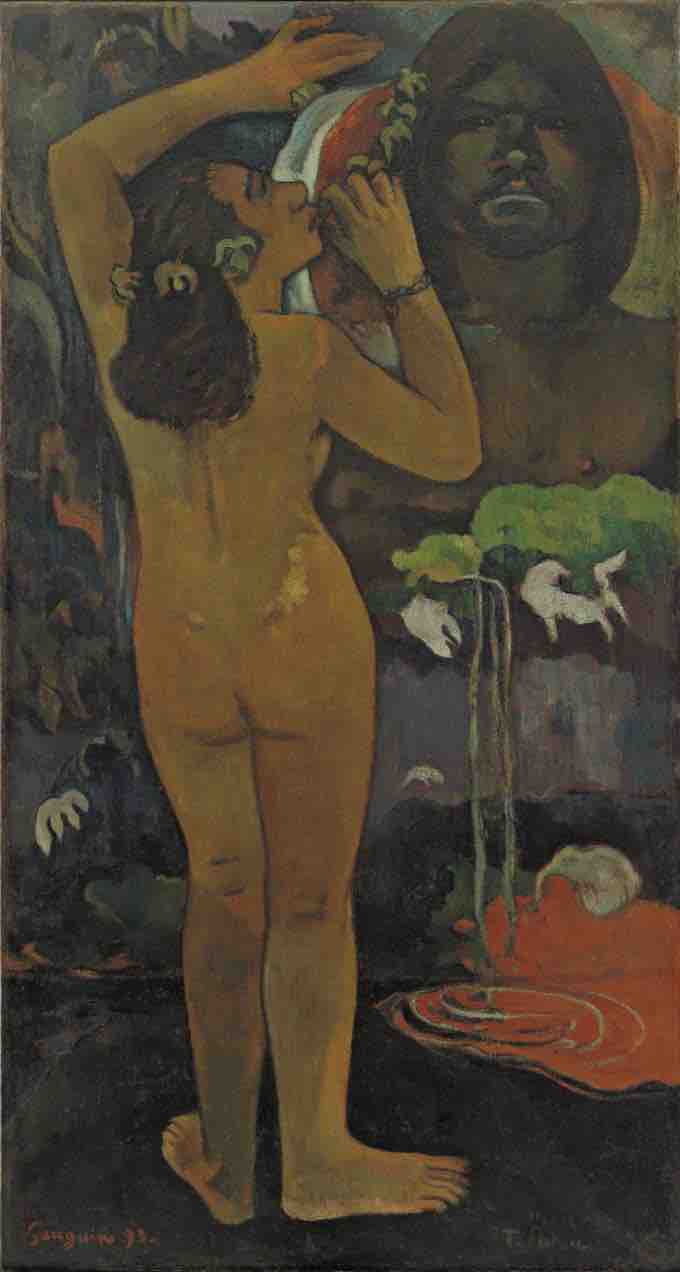

The Moon and the Earth, by Paul Gauguin, 1893

Picasso was greatly influenced by Gauguin's African inspired works like The Moon and The Earth.

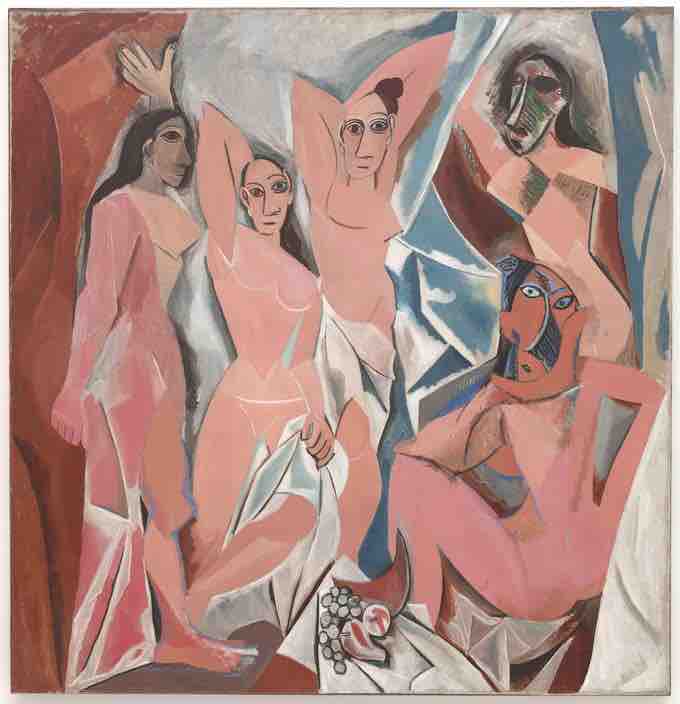

In 1907, Picasso experienced a "revelation" while viewing African art at the ethnographic museum at Palais du Trocadéro. African art influenced Picasso's painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907), especially in its treatment of the two figures on the right side of the composition . This painting is also considered a protocubist work bridging Picasso's African and Cubist periods. Other works of Picasso's African Period include the Bust of a Woman (1907, in the National Gallery, Prague); Mother and Child (Summer 1907, in the Musée Picasso, Paris); Nude with Raised Arms (1907, in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid, Spain); and Three Women (Summer 1908, in the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg).

Les Desmoiselles d'Avignon, Pablo Picasso, 1907

This work is influenced by primitivism and is considered to be one of the earliest examples of Cubist painting.

Cubism (1909–1912)

Cubism, established by Picasso and his colleague Georges Bracque, was marked by a revolutionary departure from representational art. In Cubist artwork, objects were analyzed, broken up and reassembled in an abstracted form instead of being depicted from one viewpoint. Picasso, Braque and other Cubists depicted subjects from a multitude of viewpoints to create a greater scope of context. Cubism has been considered the most influential art movement of the 20th century.

Georges Braque, Violin and Candlestick, 1910

Georges Braque, with Picasso, was one of the founders of Cubism.

Cubism had a global reach as a movement, influencing similar schools of thought in literature, music and architecture. Particular offshoots beyond France included the movements of Futurism, Suprematism, Dada, Constructivism and De Stijl, which all developed in response to Cubism. Early Futurist paintings hold in common with Cubism the fusing of the past and the present, the representation of different views of the subject pictured at the same time, also called multiple perspective, simultaneity or multiplicity, while Constructivism was influenced by Picasso's technique of constructing sculpture from separate elements. Other common threads between these disparate movements include the faceting or simplification of geometric forms, and the association of mechanization and modern life

Cubist Sculpture

Just as in painting, Cubist sculpture is rooted in Paul Cézanne's reduction of painted objects into component planes and geometric solids (cubes, spheres, cylinders, and cones). And just as in painting, it became a pervasive influence and contributed fundamentally to Constructivism and Futurism.

Cubist sculpture developed in parallel to Cubist painting. During the autumn of 1909 Picasso sculpted Head of a Woman (Fernande) with positive features depicted by negative space and vice versa. Marcel Duchamp was responsible for another extreme development inspired by Cubism. The ready-made arose from a joint consideration that the work itself is considered an object (just as a painting), and that it uses the material detritus of the world (as collage and paper mache in the Cubist construction and Assemblage). The next logical step, for Duchamp, was to present an ordinary object as a self-sufficient work of art representing only itself. In 1913 he attached a bicycle wheel to a kitchen stool and in 1914 selected a bottle-drying rack as a sculpture in its own right.