Dada was a multi-disciplinary art movement that rejected the prevailing artistic standards by producing "anti-art" cultural works. Dadaism was intensely anti-war, anti-bourgeois and held strong political affinities with the radical left. For many participants, the movement was a protest against the bourgeois nationalist and colonialist interests, which many Dadaists believed were the root cause of the war, and against the cultural and intellectual conformity—in art and more broadly in society—that corresponded to the war. Many Dadaists believed that the 'reason' and 'logic' of bourgeois capitalist society had led people into war. They expressed their rejection of that ideology in artistic expression that appeared to reject logic and embrace chaos and irrationality.

The origin of the name Dada is unclear. Some believe that it is a nonsensical word while others maintain that it originates from the Romanian artists Tristan Tzara's and Marcel Janco's frequent use of the words "da, da," meaning "yes, yes" in Romanian. Another theory posits that the name "Dada" came during a meeting of when a knife stuck into a French–German dictionary happened to point to 'dada', a French word for 'hobbyhorse'. Likely, the origin f the name Dada is another attempt to devalue a system of logic, namely that of language.

Dada began in Zurich in 1916 Key figures in the Dada movement included Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, Hans Arp and Raoul Hausmann, among others. The movement influenced later styles like avant-garde, and movements including surrealism, Nouveau réalisme, pop art and Fluxus.

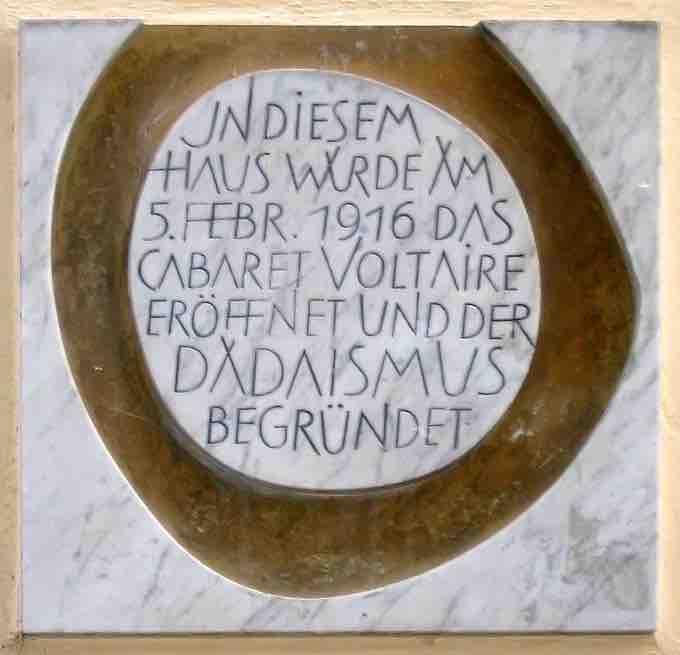

Plaque commemorating birth of Dada movement

This plaque is from the Cabaret Voltaire, the first venue where Dada artists showcased their work in 1916.

Dada was an informal international movement with participants in Europe and North America that employed all kinds of media but are known especially for collage, writing, photomontage and performance. Dadaists worked in collage, creating compositions by pasting together transportation tickets, maps, plastic wrappers and other artifacts of daily life. Dada artists also worked in photomontage, a variation on collage which utilized actual or reproductions of photographs printed in the press. In Cologne, Max Ernst used photographs taken from the front during World War I to comment on the war. Another variation on collage used by Dadaists was assemblage, the assembly of everyday objects to produce meaningful or meaningless pieces of work, including war objects and trash.

When World War I ended in 1918, most of the Zurich Dadaists returned to their home countries, while some began Dada activities in other cities.

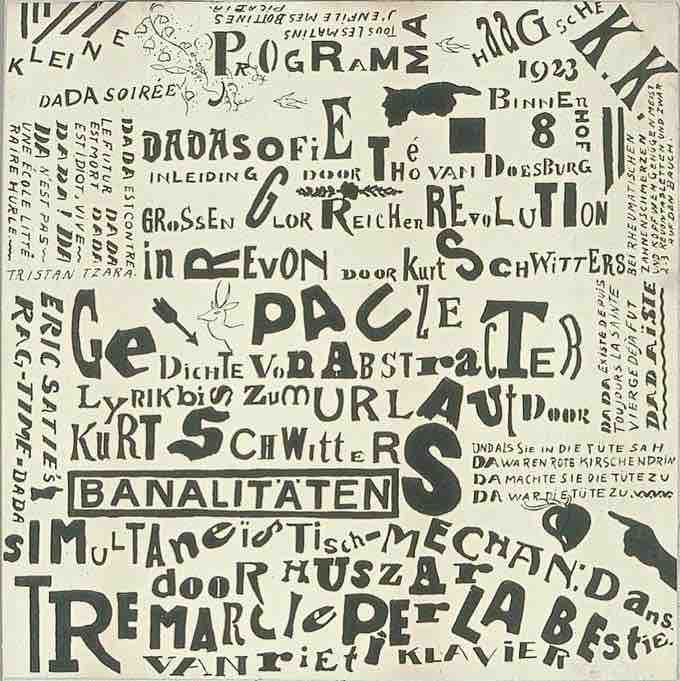

Dada poster from 1923

This poster for a Dada soiree references the medium of collage.

Like Zurich, New York City was a refuge for writers and artists from World War I. Frenchmen Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia met American artist Man Ray in New York City in 1915. The trio soon became the center of radical anti-art activities in the United States.

During this time, Duchamp began exhibiting "readymades" (everyday objects found or purchased and declared art) and was active in the Society of Independent Artists. In 1917, he submitted the now famous Fountain to the Society of Independent Artists exhibition. Initially an object of scorn within the arts community, the Fountain has since become almost canonized by some as one of the most recognizable modernist works of sculpture. The committee presiding over Britain's prestigious Turner Prize in 2004, for example, called it "the most influential work of modern art".

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain

Duchamp's appropriation of a urinal as a piece of art challenged the prevailing definition of sculpture.

By 1921, most of the original Dadists moved to Paris, where Dada experienced its last major incarnation. Inspired by Tristan Tzara, Paris Dada soon issued manifestos, organized demonstrations, staged performances and a number of journals.

While broad, the Dada movement was unstable. By 1924, artists had gone on to other ideas and movements including surrealism and social realism. Some theorists argue that Dada was the beginning of postmodern art.

Surrealism

Surrealism was a cultural movement beginning in the 1920s that sprang directly out of Dadism and overlapped in many senses. Surrealist works drew inspiration from intuition, the power of the unconscious mind and various psychological schools of thought. The work often features unexpected juxtapositions, non sequiturs and elements of surprise.

First and foremost, Surrealist artists and writers regarded their work as an expression of the philosophical movement, with the artwork being an artifact. Leader André Breton was explicit in his assertion that Surrealism was above all a revolutionary movement. Surrealism developed out of the Dada activities during World War I and the most important center of the movement was Paris. From the 1920s onward, the movement spread around the globe, eventually affecting the visual arts, literature, film, and music of many countries and languages, as well as political thought and practice, philosophy, and social theory.

As the Surrealists developed their philosophy, they believed that Surrealism would advocate the idea that ordinary and representative expression was vital and important, but that expression must be fully open to the imagination. Freud's work with free association, dream analysis, and the unconscious was of utmost importance to the Surrealists as they developed methods to liberate their imaginations.

Like Dada, Surrealism aimed to revolutionize human experience, in terms of the personal, cultural, social, and political aspects. Surrealists wanted to free people from false rationality, and also from restrictive customs and structures. Breton proclaimed that the true aim of Surrealism was "long live the social revolution, and it alone! "