Hellenistic sculpture continues the trend of increasing naturalism seen in the stylistic development of Greek art. During this time, the rules of Classical art were pushed and abandoned in favor of new themes, genres, drama, and pathos that never before were explored by Greek artists. Furthermore, the Greek artists added a new level of naturalism to their figures by adding an elasticity to their form and expressions, both facial and physical, to their figures. These figures interact with their audience in a new theatrical manner by eliciting an emotional reaction from their view, this is known as pathos.

Nike of Samothrace

One of the most iconic statues of the period, the Nike of Samothrace, also known as the Winged Victory, (c. 190 BCE) commemorates a naval victory. This Parian marble statue depicts Nike, now armless and headless, alighting onto the prow of the ship. The prow is visible beneath her feet, and the scene is filled with theatricality and naturalism as the statue reacts to her surroundings. Nike's feet, legs, and body thrust forward in contradiction to her drapery and wings that stream backwards. Her clothing whips around her from the wind and her wings lift upwards. This depiction provides the impression that she has just landed and that this is the precise moment that she is settling onto the ship's prow. In addition to the sculpting, the figure was most likely set within a fountain, creating a theatrical setting where both the imagery and the auditory effect of the fountain would create a striking image of action and triumph.

Nike of Samothrace

Marble. c. 190 BCE. Samothrace, Greece.

Venus de Milo

Also known as the Aphrodite of Melos (c. 130-100 BCE), this sculpture by Alexandros of Antioch, this sculpture is another well-known icon of the Hellenistic period. Today the goddess's arms are missing. It has been suggested that one arm clutched at her slipping drapery while the other arm held out an apple, an allusion to the Judgment of Paris and the abduction of Helen. Originally, like all Greek sculptures, the statue would have been painted and adorned with metal jewelry, which is evident from the attachment holes. This image is in some ways similar to Praxitiles's Late Classical sculpture Aphrodite of Knidos (fourth century BCE) but is considered to be more erotic than its earlier counterpart. For instance, while she is covered below the waist, Aphrodite makes little attempt to cover herself. She appears to be teasing and ignoring her viewer, instead of accosting him and making eye contact.

Alexandros of Antioch. Venus de Milo

Marble. c. 130-100 BCE. Melos, Greece.

Altered States

While the Nike of Samothrace exudes a sense of drama and the Venus de Milo a new level of feminine sexuality, other Greek sculptors explored new states of being. Instead of, as was favored during the Classical period, reproducing images of the ideal Greek male or female, sculptors began to depict images of the old, tired, sleeping, and drunk—none of which are ideal representations of a man or woman.

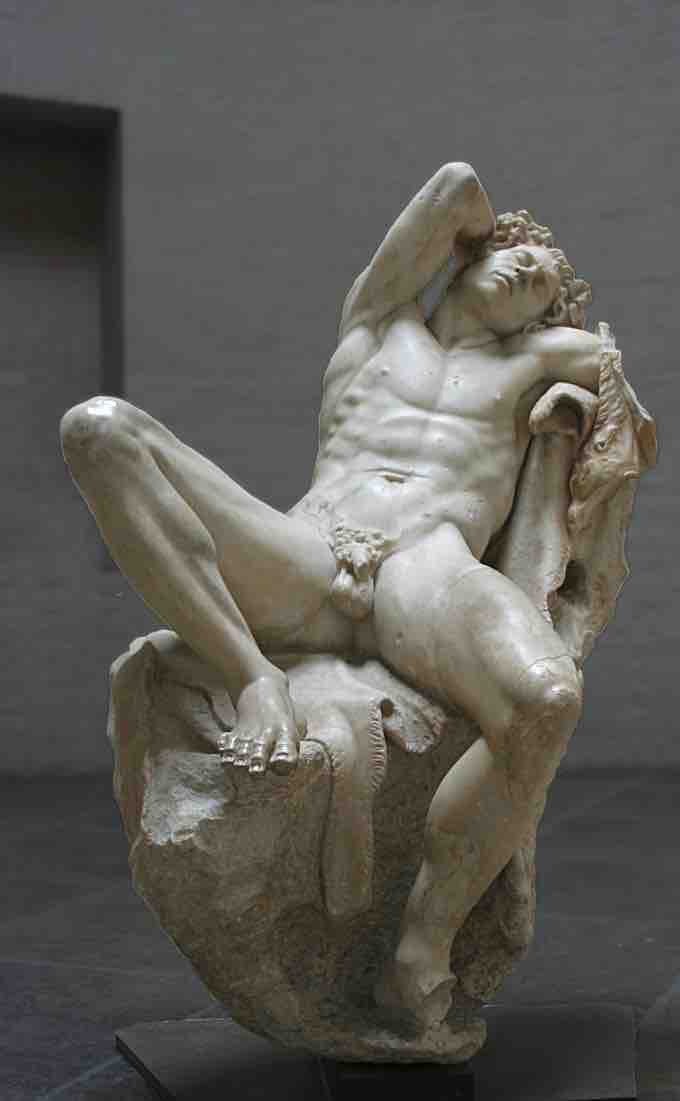

The Barberini Faun, also known as the Sleeping Satyr (c. 220 BCE), depicts an effeminate figure, most likely a satyr, drunk and passed out on a rock. His body splays across the rock face without regard to modesty. He appears to have fallen to sleep in the midst of a drunken revelry and he sleeps restlessly, his brow is knotted, face worried, and his limbs are tense and stiff. Unlike earlier depicts of nude men, but in a similar manner to the Venus de Milo, the Barberini Faun seems to exude sexuality.

Barberini Faun

Roman marble copy of Greek bronze original c. 220 BCE. Rome, Italy.

Images of drunkenness were also created of women, which can be seen in a statue attributed to the Hellenistic artist Myron of a drunken beggar woman. This woman sits on the floor with her arms and legs wrapped around a large jug and a hand gripping the jug's neck. Grape vines decorating the top of the jug make it clear that it holds wine. The woman's face, instead of being expressionless, is turned upward and she appears to be calling out, possibly to passersby. Not only is she intoxicated, but she is old: deep wrinkles line her face, her eyes are sunken, and her bones stick out through her skin.

Myron. Drunken Old Woman

Roman marble copy after Greek original. c. 200-180 BCE.

Another image of the old and weary is a bronze statue of a seated boxer. While the image of an athlete is a common theme in Greek art, this bronze presents a Hellenistic twist. He is old and tired, much like the Late Classical image of a Weary Herakles. However, unlike Herakles, the boxer is depicted beaten and exhausted from his pursuit. His face is swollen, lip spilt, and ears cauliflowered. This is not an image of a heroic, young athlete but rather an old, defeated man many years past his prime.

Seated Boxer

Bronze. c. 100-50 BCE. Rome, Italy.

Portraiture

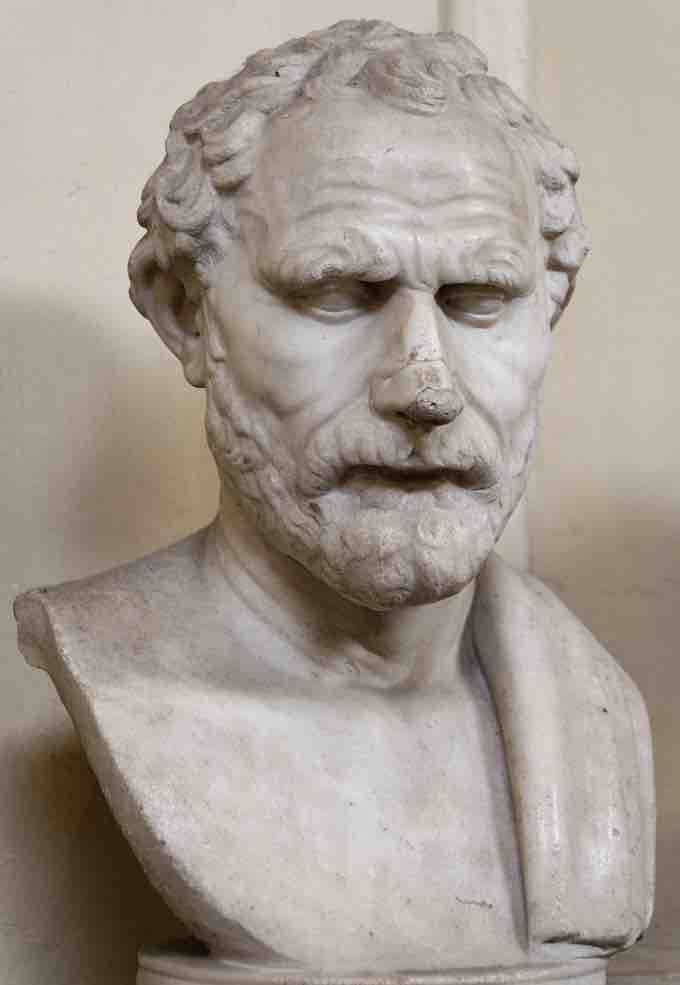

Individual portraits, instead of idealization, also became popular during the Hellenistic period. A portrait of Demosthenes by Polyeuktos (280 BCE) is not an idealization of the Athenian statesman and orator. Instead, the statue takes notes of Demosthenes's characteristic features, including his overbite, furrowed brow, stooped shoulders, and old, loose skin. Even portrait busts, often copied from Polyeuktos's famed statue, depict the weariness and sorrow of a man despairing the conquest of Philip II and end of Athenian democracy.

Polyeuktos. Demosthenes

Portrait bust, Roman copy after Greek bronze original. c. 280 BCE.

Roman Patronage

The Greek peninsula fell to Roman power in 146 BCE. Greece was a key province of the Roman Empire, and the Roman's interest in Greek culture helped to circulate Greek art around the empire, especially in Italy, during the Hellenistic period and into the Imperial period of Roman hegemony. Greek sculptors were in high demand throughout the remaining territories of the Alexander's empire and then throughout the Roman Empire. Famous Greek statues were copied and replicated for wealthy Roman patricians and Greek artists were commissioned for large-scale sculptures in the Hellenistic style. Originally cast in bronze, many Greek sculptures that we have today survive only as marble Roman copies. Some of the most famous colossal marble groups were sculpted in the Hellenistic style for wealthy Roman patrons and for the imperial court. Despite their Roman audience, these were purposely created in the Greek style and continued to display the drama, tension, and pathos of Hellenistic art.

Laocoön and His Sons

Laocoön was a Trojan priest of Poseidon who warned the Trojans, "Beware of Greeks bearing gifts," when the Greeks left a large wooden horse at the gates of Troy. Athena or Poseidon (depending on the story's version), upset by his vain warning to his people, sent two sea serpents to torture and kill the priest and his two sons. Laocoön and His Sons, a Hellenistic marble sculpture group (attributed by Roman historian Pliny the Elder to the sculptors Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus from the island of Rhodes) was created in the early first century CE to depict this scene from Virgil's epic The Aeneid.

Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus of Rhodes. Laocoön and His Sons.

Marble. Early first century BCE.

Similar to other examples of Hellenistic sculpture, Laocoön and His Sons depicts a chiastic scene filled with drama, tension, and pathos. The figures writhe as they are caught in the coils of the serpents. The faces of the three men are filled with agony and toil, which is reflected in the tension and strain of their muscles. Laocoön stretches out in a long diagonal from his right arm to his left as he attempts to free himself. His sons are also entangled by the serpents, and their faces react to their doom with confusion and despair. The carving and detail, the attention to the musculature of the body, and the deep drilling, seen in Laocoön's hair and beard, are all characteristic elements of the Hellenistic style.

Laocoön and His Sons (detail of Laocoön’s face)

Farnese Bull

The Farnese Bull (c. 200-180 BCE), named for the patrician Roman family who owned the statue in the Italian Renaissance, is believed to have been created for the collection of Asinius Pollio, a Roman patrician. Pliny the Elder attributes the statue to the artists and brothers Apolllonius and Tauriscus of Trallles, Rhodes. The colossal marble statue, carved from a single block of marble, depicts the myth of Dirce, wife of the King of Thebes, who was tied to a bull by the sons of Antiope to punish her for mistreating their mother. The composition is large and dramatic, and demands the viewer to encircle it in order to view and appreciate the narrative and pathos from all angles. The various angles reveal different expressions, from the terror of Dirce, to the determination of Antiope's sons, to the savagery of the bull.

Apollonius and Tauriscus of Tralles, Rhodes. Farnese Bull.

Marble. c. 200-180 BCE.