Temple of Zeus at Olympia

The Temple of Zeus at Olympia is a colossal ruined temple in the center of the Greek capital Athens that was dedicated to Zeus, king of the Olympian gods. Its plan is similar to that of the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina. It is hexastyle, with six columns across the front and back and 13 down each side. It has two columns directly connected to the walls of the temple, known as in antis, in front of both the entranceway (pronaos) and the inner shrine (opisthodomos). Like the Temple of Aphaia, there are two, two-story colonnades of seven columns on each side of the inner sanctuary (naos).

Temple of Zeus at Olympia

Wilhelm Lübke's illustration of the Temple as it might have appeared in the fifth century BCE.

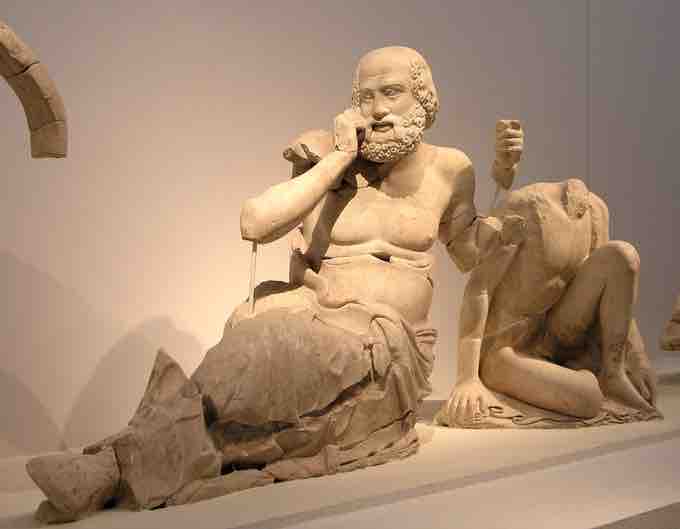

The pedimental figures are depicted in the developing Classical style with naturalistic yet overly-muscular bodies. Most of the figures are shown with the expressionless faces of the Severe style. The figures on the east pediment await the start of a chariot race, and the whole composition is still and static. A seer, however, watches it in horror as he foresees the death of Oenomaus. This level of emotion would never be present in Archaic statues and it breaks the Early Classical Severe style, allowing the viewer to sense the forbidding events about to happen.

Seer from the east pediment, Temple of Zeus. Marble. c. 470-455 BCE. Olympia, Greece.

The level of emotion on the seer's face would never be present in Archaic statues and it breaks the Early Classical Severe style, allowing the viewer to sense the forbidding events about to happen.

Unlike the static composition of the eastern pediment, the Centauromachy on the western pediment depicts movement that radiates out from its center. The centaurs, fighting men, and abducted women struggle and fight against each other, creating tension in another example of an early portrayal of emotion. Most figures are depicted in the Severe style. However, some, including a centaur, have facial features that reflect their wrath and anger.

Centauromachy. c. 460 BCE.

West pediment, Temple of Zeus at Olympia.

The twelve metopes over the pronaos and opisthodomos depict scenes from the twelve labors of Herakles. Like the development in pedimental sculpture, the reliefs on the metopes display the Early Classical understanding of the body. Herakles's body is strong and idealized, yet it has a level of naturalism and plasticity that increases the liveliness of the reliefs. The scenes depict varying types of compositions. Some are static with two or three figures standing rigidly, while others, such as Herakles and the Cretan Bull convey a sense of liveliness through their diagonal composition and overlapping bodies.

Athena and Herakles depicting the Stymphalian Birds. c. 460 BCE

Temple of Zeus at Olympia. This metope fragment depicts Herakles with relatively calm body language.

Herakles and the Cretan Bull. c. 460 BCE.

Temple of Zeus at Olympia. This metope fragment depicts Herakles in a more dynamic and emotive pose.

Kritios Boy

A slightly smaller-than-life statue known as the Kritios Boy was dedicated to Athena by an athlete and found in the Perserchutt of the Athenian Acropolis. Its title derives from a famous artist to whom the sculpture was once attributed. The marble statue is a prime example of the Early Classical sculptural style and demonstrates the shift away from the stiff style seen in Archaic kouroi. The torso depicts an understanding of the body and plasticity of the muscles and skin that allows the statue to come to life. Part of this illusion is created by a stance known as contrapposto. This describes a person with his or her weight shifted onto one leg, which creates a shift in the hips, chest, and shoulders to create a stance that is more dramatic and naturalistic than a stiff, frontal pose. This contrapposto position animates the figure through the relationship of tense and relaxed limbs. However the face of the Kritios Boy is expressionless, which contradicts the naturalism seen in his body. This is known as Severe style. The blank expressions allow the sculpture to appear less naturalistic, which creates a screen between the art and the viewer. This differs from the use of the Archaic smile (now gone), which was added to sculpture to increase their naturalism. However, the now empty eye sockets once held inlaid stone to give the sculpture a lifelike appearance.

Kritios Boy, Marble. c. 480 BCE. Perserchutt, Acropolis, Athens, Greece.

This marble statue is a prime example of the Early Classical sculptural style and demonstrates the shift away from the style seen in Archaic kouroi.

Polykleitos

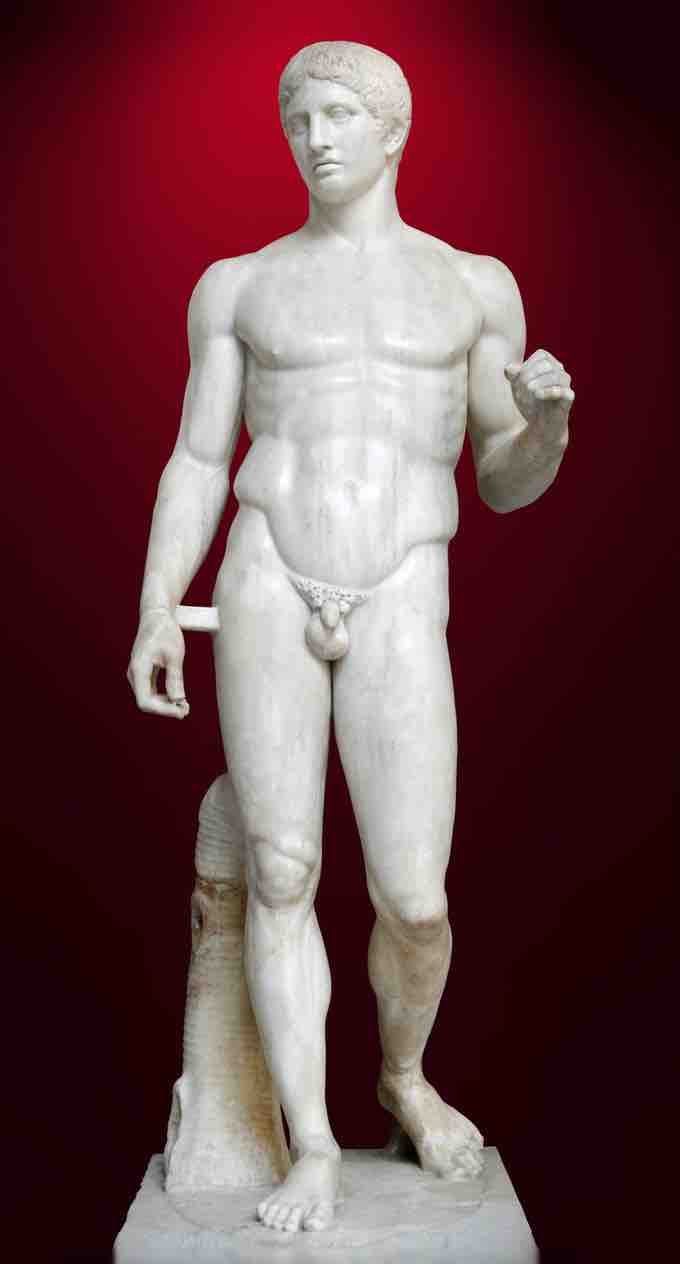

Polykleitos was a well-known Greek sculptor and art theorist during the early- to mid-fifth century BCE. He is most renowned for his treatise on the male nude, known as the Canon, which describes the ideal, aesthetic body based on mathematical proportions and Classical conventions such as contrapposto. His Doryphoros, or Spear Bearer, is believed to be his representation of the Canon in sculpted form. The statue depicts a young, well-built, soldier holding a spear in his left hand with a shield attached to his left wrist. Both military implements are now lost. The figure has a Severe-style face and a contrapposto stance. In another development away from the stiff and seemingly immobile Archaic style, the Doryphoros's left heel is raised off the ground, implying an ability to walk.

Polykleitos, Doryphoros. Roman marble copy of a Greek bronze original c. 450 BCE.

Polykleitos's Doryphoros, or Spear Bearer, is believed to be his representation of the Canon in sculpted form.

This sculpture demonstrates how the use of contrapposto creates an S-shaped composition. The juxtaposition of a tension leg and tense arm and relaxed leg and relaxed arm, both across the body from each other, creates an "S" through the body. The dynamic power of this composition shape places elements -- in this case the figure's limbs -- in opposition to each other and emphasizes the tension this creates. The statue, as a visualization of Polykletios's canon, also depicts the Greek sense of symmetria, the harmony of parts, seen here in the body's proportions.