History

Djenné is a town and an urban commune in the inland Niger Delta region of central Mali. Between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries, Djenné was a leading commercial center in West Africa. As a major terminal in the gold, salt, and slave trade of the trans-Saharan trade route, it flourished for several centuries. Much of the trans-Saharan trade in goods that moved in and out of Timbuktu passed through Djenné.

Djenné was also a chief center of Sudanese Islam in this period. Its Great Mosque was an important center of religious life. However, the rise of the Mali Empire in the thirteenth century contributed to its steady decline, and its brief period of dominance came to an end when it was reduced to a tributary state. Between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries, Djenné and Timbuktu were both important trading posts in a long distance trade network. Both towns became centers of Islamic scholarship, and in the seventeenth century Djenné was a thriving center of learning.

The town is famous for its distinctive Sudanese-style mud-brick architecture, most notably the Great Mosque. To the south of the town is Djenné-Jéno, the site of one of the oldest known towns in sub-Saharan Africa. Djenné together with Djenné-Jéno and the Great Mosque were designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1988.

Architecture

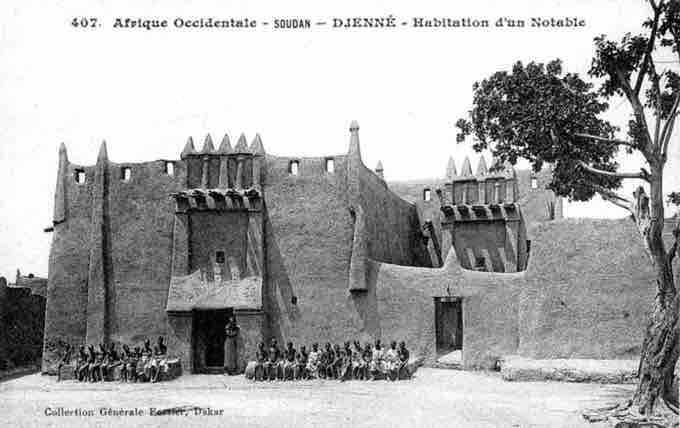

Nearly all of the buildings in the town consist of load-bearing walls made from sun-baked mud bricks coated with mud plaster. Because the walls are load-bearing, doors and windows must be small and few in number, often resulting in dark interiors. In Djenné, the mud-brick buildings need to be re-plastered with mud at least every other year. Even then, the annual rains can cause serious damage. Older buildings are often entirely rebuilt.

Traditional houses are two stories with flat roofs, built around a small central courtyard. Built with imposing façades with pilaster-like buttresses, many have elaborate arrangements of pinnacles forming a parapet above the entrance door. The façades are decorated with bundles of rodier palm sticks, called toron, that project away from the wall and serve as a type of scaffolding. Ceramic pipes extend from the roofline to protect the walls from rain water damage. Many houses built before 1900 are in the Toucouleur-style and have a massive covered porch set between two large buttresses. These houses generally have a single small window onto the street set above the entrance door.

A house in Djenné

Many houses in Djenné are built with Toucouleur–style façades.

The Great Mosque

The rise of Islam witnessed a steady construction of mosques in the region. Sudano-Sahelian architecture reproduces the sacred architecture of Mecca in mud brick and other local materials. Similar styles are evident in mosques in Ghana and Tunisia.

The Great Mosque of Djenné is the largest mud brick or adobe building in the world and is considered by many architects to be the greatest achievement of the Sudano-Sahelian architectural style, with definite Islamic influences. As well as being the center of religious and community life, it is one of the most famous landmarks in Africa. The actual date of construction of the original mosque is unknown, but dates as early as 1200 and as late as 1330 have been suggested.

Falling into disrepair over the centuries, the French administration arranged for the original mosque to be rebuilt in 1907. The position of at least some of the outer walls appears follows those of the original mosque, but it is unclear as to whether the columns supporting the roof kept to the previous arrangement. What was almost certainly novel in the rebuilt mosque was the symmetric arrangement of three large towers in the qibla wall. There has been debate as to what extent the design of the rebuilt mosque was subject to French influence.

Great Mosque of Djenné

Originally built in the thirteenth or fourteenth century, the Great Mosque seen today was completed in 1907.

The qibla, which face the direction of Mecca, is dominated by three large, box-like minarets jutting out from the main wall. Each minaret is topped with an ostrich egg. The central minaret is approximately 48 feet tall. The eastern wall is roughly three feet thick and is strengthened on the exterior by eighteen buttresses. The corners are formed by rectangular shaped buttresses topped by pinnacles.

The prayer hall, measuring about 85 by 164 feet, occupies the eastern half of the mosque behind the qibla wall. The mud-covered, rodier-palm roof is supported by nine interior walls running north-south which are pierced by pointed arches that reach up almost to the roof. In the prayer hall, each of the three towers in the qibla wall has a niche or mihrab. The imam conducts the prayers from the mihrab in the larger central tower. A narrow opening in the ceiling of the central mihrab connects with a small room situated above roof level in the tower. To the right of the mihrab in the central tower is a second niche, the pulpit or minbar, from which the imam preaches his Friday sermon.