Art of Ancient Africa

African art constitutes one of the most diverse legacies on earth. Though many casual observers tend to generalize "traditional" African art, the continent consists of a wide diversity of people, societies, and civilizations, each with a unique visual culture. As the birthplace of the human species, Africa is the home of some of the oldest art forms on Earth. Because much of these artworks were produced in wood and other highly perishable materials, only a small number of artworks produced before the nineteenth century survive. Examples include terra cotta sculptures, rock carvings, and architectural ruins.

The art of ancient African was just as diverse as its cultures, languages, and political structures. Most cultures preferred abstract and stylized forms of humans, plants, and animals, but their approaches varied greatly. That said, some cultures preferred more naturalistic depictions of human faces and natural other forms.

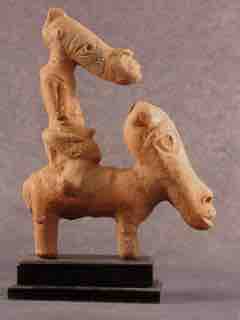

The Nubian Kingdom of Kush in modern Sudan was in close and often hostile contact with Egypt, and produced monumental sculpture mostly derivative of styles that did not lead to the north. In West Africa, the earliest known sculptures are from the Nok culture which thrived between 500 BCE and 500 CE in modern Nigeria, with clay figures typically with elongated bodies and angular shapes.

Nok rider and horse 53 cm tall (1,400 to 2,000 years ago)

The Nok culture appeared in Nigeria around 1000 BCE and vanished under unknown circumstances around 500 CE in the region of West Africa. This region lies in Northern and Central Nigeria. Its social system is thought to have been highly advanced. The Nok culture was considered to be the earliest sub-Saharan producer of life-sized terra cotta.

Human and Animal Forms

The human figure has always been a primary subject of African art, and this emphasis even influenced certain European traditions. For example, in the fifteenth century, Portugal traded with the Sapi culture near Côte d'Ivoire in West Africa, whose residents created elaborate ivory saltcellars that were hybrids of African and European designs. This was most notable in the addition of the human figure, as the human figure typically did not appear in Portuguese saltcellars. European subjects can be distinguished by their clothing and hairstyles. The human figure might symbolize the living or the dead. Possible subjects include chiefs, dancers, drummers, or hunters. They might even be anthropomorphic representations gods or ancestors or have other votive functions.

Saltcellar

Saltcellar by an Edo or Yoruba artist representing a Portuguese man, decorated with horses among geometric patterns. Sixteenth century.

Even before contact with the Europeans, some African cultures opted for naturalistic depictions over the dominant preference for abstraction and stylization. This preference can be seen in the Yoruba portrait bronzes of Ile-Ife, which include indented and incised details that might represent ritual scarification.

Yoruba head

Bronze. Ile-Ife. Twelfth century.

The bronzes of Igbo-Ukwu pay special attention to detail depicting birds, snails, chameleons, and other natural aspects of the world. The objects are so fine that small insects were included on the surfaces of some. Each of these bronzes were produced in one piece.

Ceremonial vessel

Bronze. Igbo-Ukwu. Ninth century.

Architecture and Saharan Rock Art

Architectural ruins in locations such as Mali and Zimbabwe demonstrate the popularity of load-bearing architecture in such diverse materials as adobe and stone. In areas such as Mali and Igbo-Ukwu, buildings constructed from perishable materials continue to be built or rebuilt in traditional styles that provide a window into the past.

Painted and incised scenes on caves, boulders, and other rock formations in the Sahara provide a glimpse of life in this now-desert region when it was a grassland with ample water supplies over 10,000 years ago. Imagery include scenes such as farming, hunting, and swimming.